“The knowledge of cooking does not come pre-installed in a vagina. Cooking is learned. Cooking is a life skill that men and women should both ideally have.”

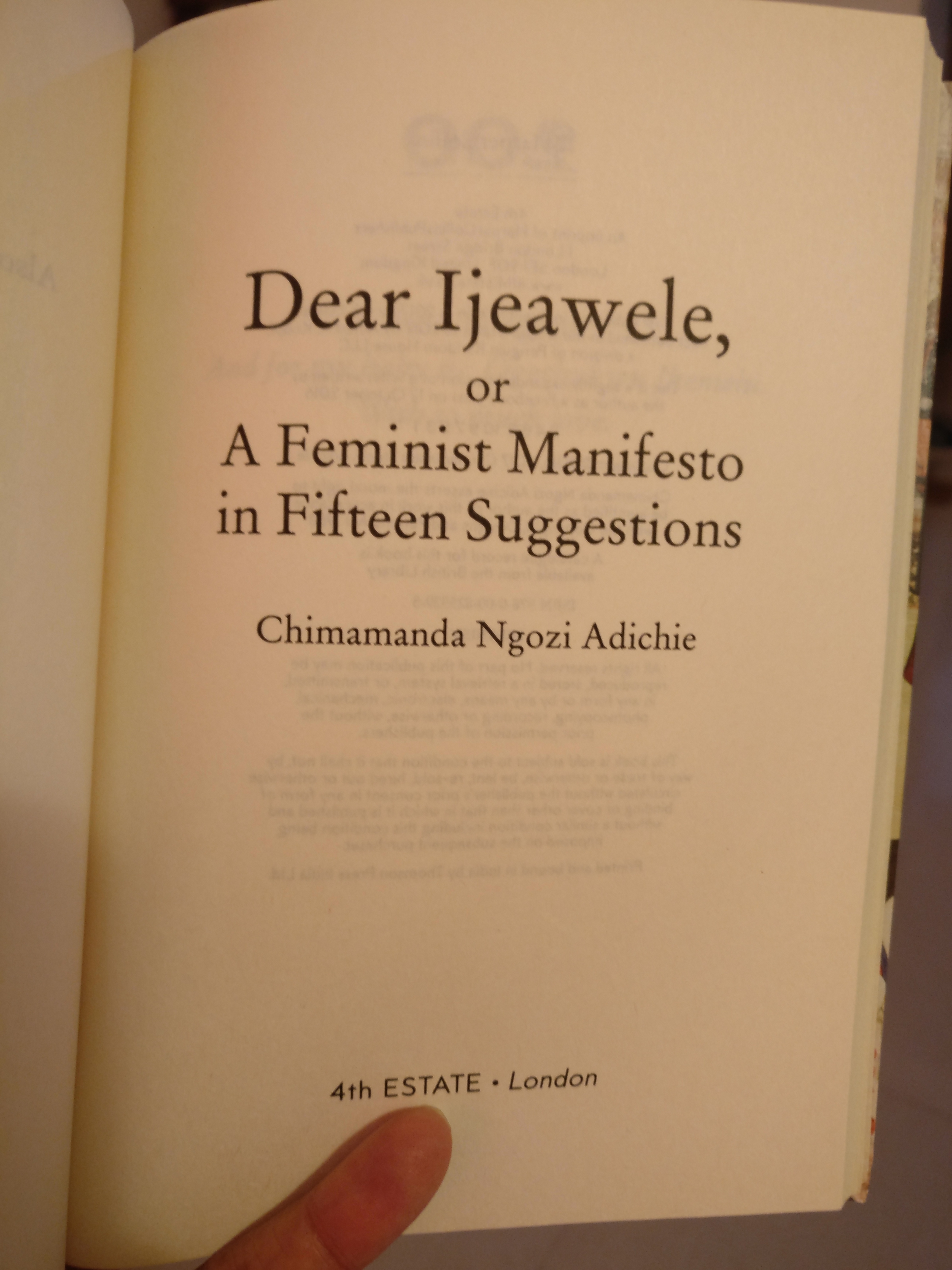

These are the words of the Nigerian writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her book “Dear Ijeawele, or A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions”. The book was born when a friend asked Adichie for her advice on how to raise her baby girl, Chizalum, a feminist. Adichie puts together a simple list of invaluable suggestions for every woman and every girl to become more empowered and independent. She highlights some very basic choices that a woman makes in her life, some out of ignorance and some because of societal norms and pressures. Decades of conditioning has made the society assign lopsided roles for both men and women in domestic as well as workplace scenario. Adichie’s list is a gentle reminder that gender roles restrict to only biological necessities like giving birth or breastfeeding a baby and all the other duties and responsibilities are necessarily not just a woman’s.

I can relate to several instances that she brings up in the book well as many African traditions, customs and social norms match those of Indian. While in Indian context there has been a massive change in the last couple of decades, there is still a large part of the country both in urban as well as rural areas where the subtle gender expectations still exist.

I remember some years ago, when an aunt and uncle were discussing ‘prospective’ brides for their son, they approved of girls from certain districts of Andhra Pradesh but not from certain others. The reason for disapproving girls from those areas was that girls who came from so and so district were very ‘powerful’. A little research revealed that people from these districts were landholders and were hence well educated and women usually owned properties and they were very good with financial decisions at home. Hence there was an imminent threat that they would ‘overpower’ their husbands hence making them ‘hen-pecked’. But if you ask me, these are characteristics of an excellent, skilled and talented woman who, if given an opportunity, would take care of the family successfully. The couple would raise their sons and daughters with equal status. But conditioning makes us feel uncomfortable around any woman who is strong.

I have witnessed over the years similar family conversations that surround the son ‘allowing her daughter-in-law to work’ or ‘We gave our daughter basic education. After her marriage, it is up to the husband to let her continue or not’ or ‘Oh! My son is a very busy doctor. He wants a wife who can take care of home and children’ and the like.

When we were growing up, somebody or the other in the family would advise my mother, “Don’t let your girls choose whatever they want. Some decisions are for parents to make.” Well, if it is only about choosing a school or picking which movie you want to go, it is not dangerous. But if the choice is about who you want to marry or what career you want to choose or whether you want to work or not, the choice HAS to be yours. And thankfully our parents seldom interfered in our lives.

Adichie’s manifesto throws up many such instances which are from a domestic setting and workplace, prejudices expressed through vocabulary, cultural connotations, gender manifestations etc. Her advice to her friend (and all of us with daughters and sons) ranges from personal choices women should make for themselves to the necessity of financial freedom, respecting culture and traditions selectively and teaching her daughter the importance of reading books.

Adichie’s style is very unpretentious, assertive, gentle and evocative. The language is simple and straightforward and the book opens up a series of thoughts and experiences from your own life. Her advice is simple and does not encourage, suggest or express authority or control in the name of gender but simply reminds every one that we are human beings and everyone is entitled to his/her freedom.