Conversations related to the inevitability and permanence of death are considered ominous and are often avoided, postponed or in many cases, ignored. We pretend that old age and death are non-existent and even a mild reference to them upset us. People are generally reluctant about writing a will, saving up for unforeseen illnesses or even letting go of things.

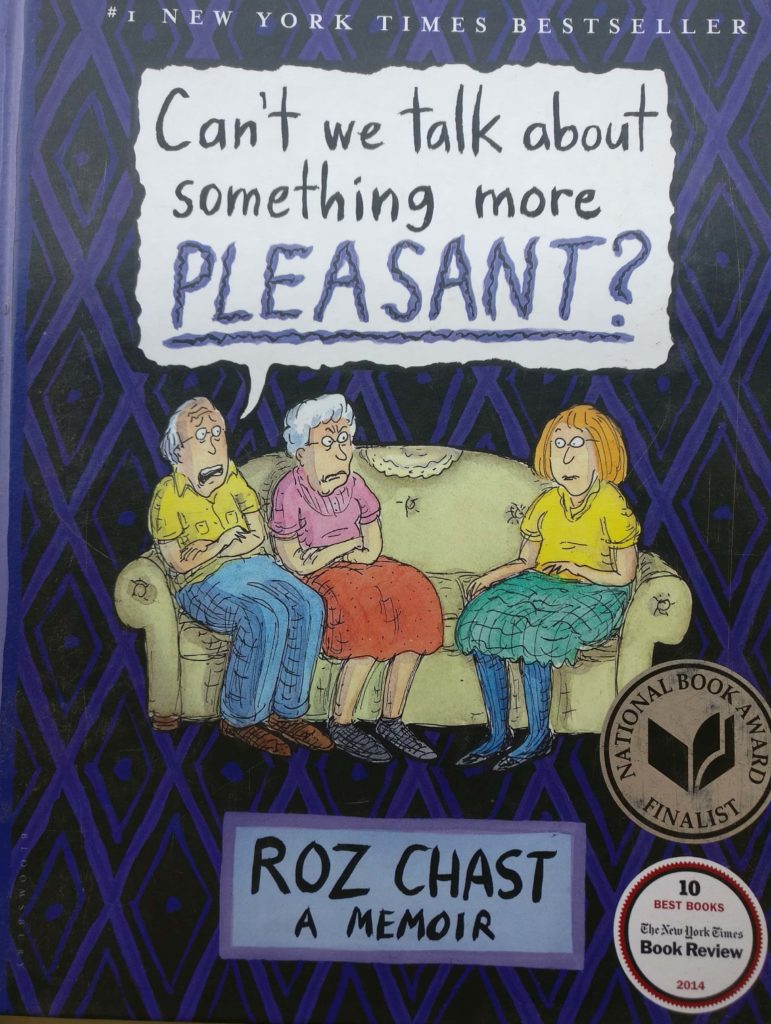

In “Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant”, Rosalind “Roz” Chast recounts her personal experiences with her elderly parents while taking care of them during the last few years of their life. Roz Chast, a New York journalist and cartoonist, narrates vividly her observations and her experiences taking care of her parents in Brooklyn. Her Jewish parents migrated to United States at the turn of the 19th century. George Chast, her father, was a high school Spanish and French teacher and her mother, Elizabeth was an assistant principal in an elementary school. They worked hard and lived a very humble, frugal life. Chast, their only daughter, after she moved out of her parents’ house, withdrew from any involvement with her parents for several years, till one day she dropped in their apartment for a casual visit. Her visit throws her in to a sequence of unavoidable responsibilities that she doesn’t expect and draws her into the life of her parents who are by then well into their old age. Chast’s memoir takes you through her bitter-sweet journey with her parents, especially during the last decade of their lives.

The memoir starts with Chast’s concerns about her parent’s future and the conversations she has with them which they tactfully avoid answering. Chast puts this into perspective and draws the title of her book from the general reluctance that people exhibit with subjects like death, old age and even religion. Chast sums it up in the “Introduction’ with a statement “Maybe they believe that if they just held on to each other really tightly for eternity, nothing would ever change”.

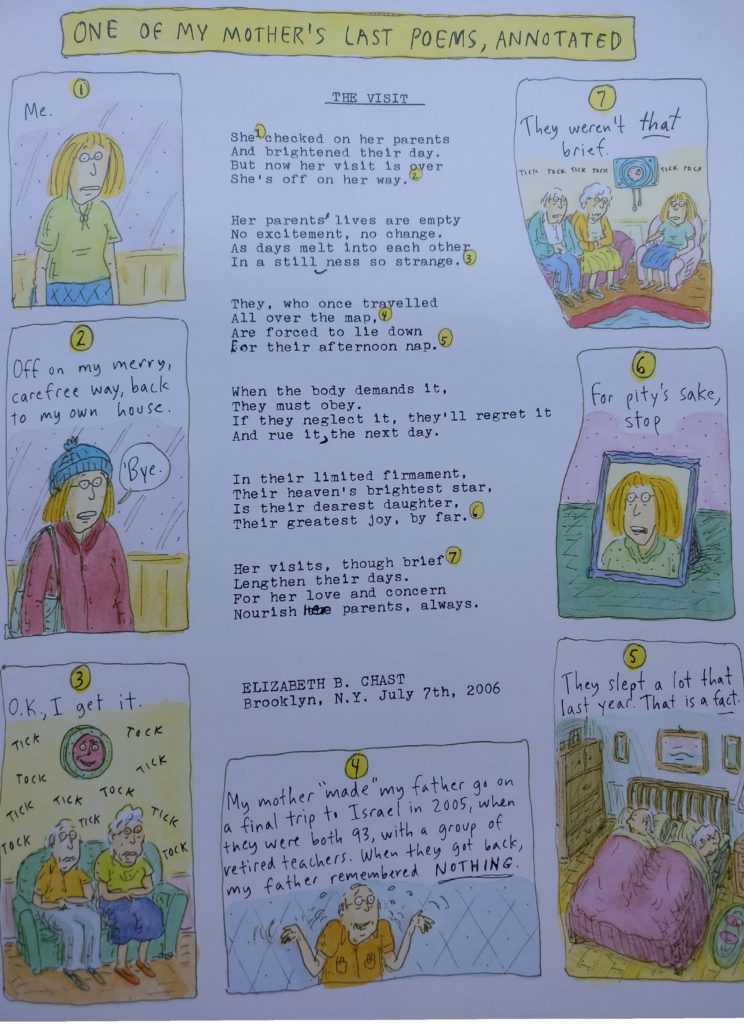

What is refreshingly different is Chast’s perspective about eldercare. In a world where taking care of one’s parents is highly romanticised, Chast’s very straightforward narration puts you off balance. The first two pages set the subject matter in place and then what follows is a sequence of events that unfold in each page, through her vividly descriptive cartoons, sketches, notes and photographs. Each cartoon abounds with visual as well as verbal expression and as she fills the pages with her humorous and descriptive details of her life with her aging parents, you are left with sketches and images of your own similar experiences with your parents or a member of your extended family. It is hard to judge Chast for her tempers, her occasional outbursts and her reluctance once in a while dealing with her parents. Moments of frustration are soon washed over by her extreme love for them and concern for their well-being. The memoir takes you back and forth between the present episodes and her childhood recollections. Chast is very candid in her descriptions of some embarrassing moments during her teenage years growing up with her parents, the shabbiness of their house, her mother’s tantrums and her father’s anxieties. She doesn’t mince her words when she describes her helplessness whenever she found it too frustrating dealing with her parents. She takes her readers down the memory lane, from revealing her life as a shy introverted kid to being an unhappy teenager, growing up in Brooklyn. She describes her parents as hardworking, loving and very humble about their living conditions. As parents who have seen the Great Depression, they instilled in her the lessons of frugality. But what Roz remembers the most was her parents’ indifference towards her needs and emotions. Her mother, throughout the memoir, is shown as a having ‘fearsome temper’ which she called ‘blasts from Chast’. In the book she describes her father as ‘tentative and gentle’; her mother as ‘critical and uncompromising’. While her mother made all the decisions at home, including those of Roz’s personal choices, her father merely accepted his wife’s decisions and succumbed to them. It was always a gruelling task to persuade her mother to see a doctor, even in case of a medical emergency as she had an aversion to doctors and hospitals. She was often heard saying, “I am built like a peasant”. She refused to give up on life and kept her husband afloat too as she battled with her aging body and the ticking time. Her grit and determination to fight death was phenomenal and it is very easy to see how the couple was perfect for each other – Elizabeth, strong and determined; George, frail and submissive. But Roz Chast is very candid about her parent’s feelings for their only daughter and their own love for each other.

Roz’s memoir is interspersed with emotions, positive and negative, which well up in her as she takes care of her aging parents. Living in Connecticut, she would make frequent trips to Brooklyn to either spend time with her parents or rush them to the hospital whenever there was a mishap or emergency. The latter increased as the years pass by, which persuaded her to make a decision to keep her parents in assisted living facilities. She soon realised that convincing them to live in such homes was not easy either as her parents found them a ‘hell hole’ and detested the fact that they were not called ‘residents’ but referred to as ‘inmates’. With myriads of complaints and inconveniences, accompanied with rapidly dwindling finances(a fact that her parents were happily unaware of), Chast and her parents swim through their days, assisted by hospice care, nurses and the staff of ‘the Place’.

With senility at its peak, dementia, aging bodies and dwindling mental faculties, George and Elizabeth stand for their ilk, who take things in their stride, with the will to live on their own and a hope to survive against all odds.

Your review brings out a deep insight into this beautiful and poignant book. I will pass this link to friends who I know like the book as much!

Look forward to more reviews from you :)!

Thank you!

Insightful

Thank you