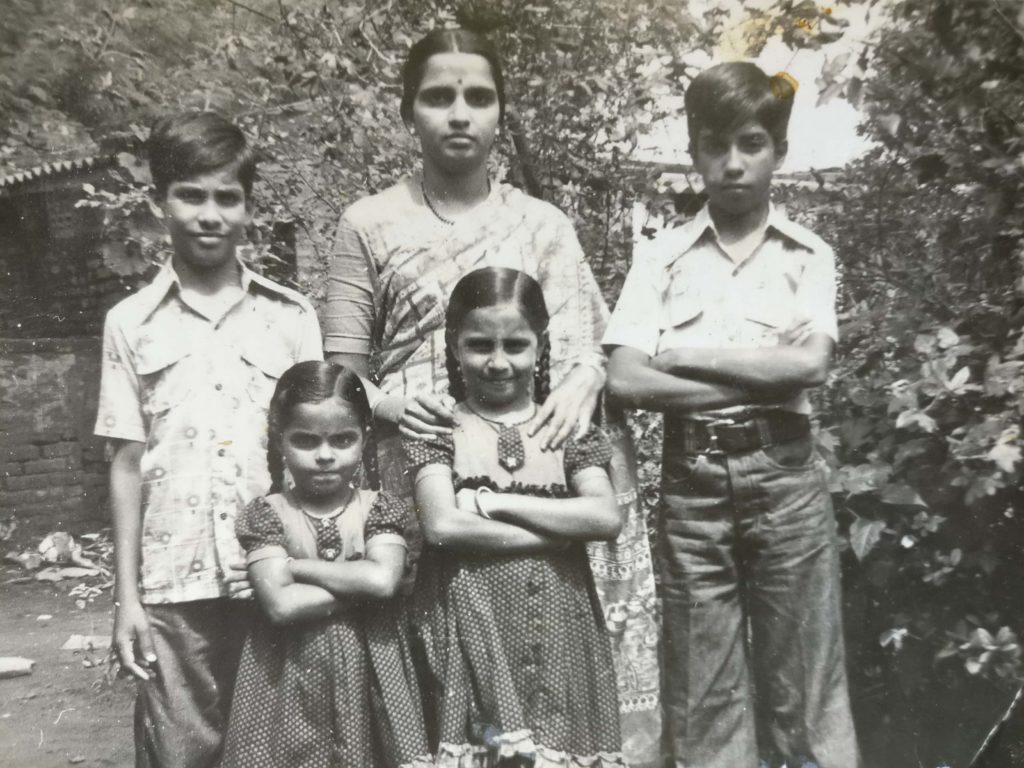

My sister and I were 6 and 8 when my father, a doctor, was invited to work in Iraq. Since we were still very young, my parents decided to take us with them leaving behind my two elder brothers with my grandparents. That was in 1979.

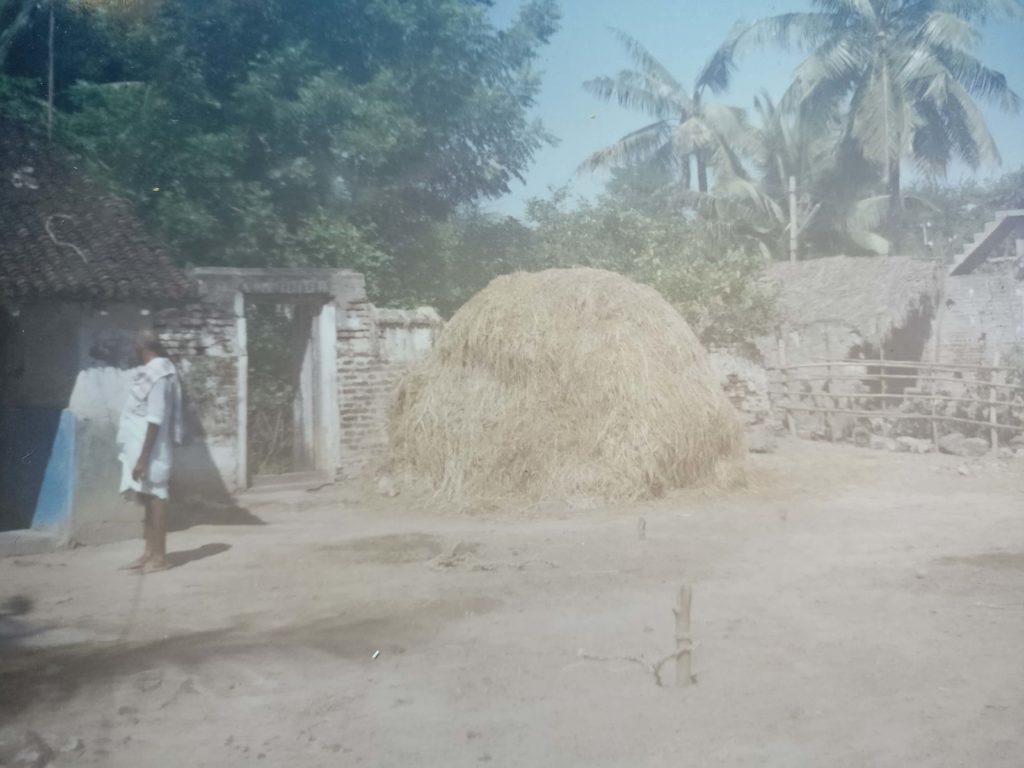

My father was first posted in Al Sahein, a small village in the wetlands of Southern Iraq. Al Sahein stood on the marshes between the two great rivers Tigris and Euphrates. The ‘Marsh Arabs’ or Ma’dan as they were called, built their houses using reeds of grass which grew abundantly in the area. My father’s hospital and the living quarters which were probably the only concrete buildings in the village, were both built on water like all the other houses in the village. People used boats to navigate around and their lives depended on the marshes for food and shelter. The local population showed immense respect for doctors who worked in the village hospital. They went out of their way to help us settle down and adjust to the new life. Though the region was under-developed, with the support and affection of the local people, we lived there comfortably for around six months before my father was posted to another place. Over the years the marshes were systematically drained and people were forced to move to other places during the political regime of Saddam Hussein. Efforts are now underway to restore this unique heritage site and make it a tourism destination. The Ma’dans are gradually coming back after many years, picking up the remnants of their lost life and creating a new livelihood for themselves.

My father was later posted in various other small towns like Qalat Salah, Samāwah and of course the city of Baghdad but everywhere we went, we made local friends with whom we had very good association till we left the country in 1984. Qalat Salah and Samāwah didn’t have English schools and my parents taught us at home from books brought from India. The people of the country fascinated us as children and as my parents were quite adaptable to new environment and cultures, we were very receptive to the local experiences. Neither the heat, nor the strange neighbourhoods deterred us from having fun. We had many local friends with whom we spoke in broken Arabic punctuated with our highly creative use of non-verbal communication. It worked most of the times but an occasional lapse in our communication would bring out a volley of interesting swear words from both sides that would bring all interaction to a sudden halt only to rekindle our friendship again after a few days.

We were particularly fascinated with their local breads khubz (a tandoori flat bread) and samoon (a long loaf of bread), which were their staple. My sister and I often helped our land lady of our Samāwa home, make khubz in her traditional mud oven called tannour. It was enchanting to watch her skilfully knead the dough and pat them into huge flat rounds and stick them inside the hot oven. We would often hover around their kitchen to catch a glimpse of the family (the parents with their 10 children) as they sat around a huge plate of their favourite breads and delicious curries, chatting and generally having a great family time. We were sometimes treated to a couple of freshly baked samoon or warm khubz that we immediately devoured with a dollop of butter on them.

The Iraqis we met or befriended during those few years were very kind and generous. Several times when we travelled by local taxis and buses, the drivers would refuse to take money from my father as he would speak to them in bits and pieces of Arabic that he picked up as a doctor. Throughout the journey they would talk about life in Iraq and my father would share information about India and its traditions and culture. Friends from my father’s hospital also regularly visited us and my mother would serve them some of our Indian delicacies that they would literally lick off the plates. Many of them loved Mohamed Rafi, the legendary Indian playback singer of Hindi movies. They would request my father to share with them some of the audio tapes of his famous songs or would copy them on to new tapes using a tape recorder. Though they were fascinated and curious with our way of life and dressing, they were seldom disrespectful. My parents had many Indian friends and over the weekends (Friday was their day off) we would meet them for lunches and dinners. But the memories of our Iraqi friends, our playmates, our silly, stunted bilingual conversations with them, the bitter-sweet taste of raw dates, the beautiful sound of Arabic is what we cherish the most.

Our experiences staying in Iraq for two years shaped our world view immensely. The friendships and associations that we made back then left an indelible mark on our mind; we learned that people everywhere were the same; they loved and hated the same things, had the same family values, and went through the exact same rigors of life within their political, geographical and social limitations. We had seen the consequences of war and how it had changed lives forever. Curfews, night patrols, emergency sirens in the middle of the night, bullet shells everywhere and many more such experiences are so vividly etched on my mind. We had seen the effect of war on families around us – bodies of soldier sons returning home from war, young boys forced into training camps and from there to the battle fields; poverty, fear and unpredictable future in front of them. These experiences of human suffering and death and decay is imprinted in our psyche and taught us young that life is precious, that we are among some of the few fortunate souls who have been given the gift of healthy and happy living and that everyone is entitled to a healthy and prosperous life. We often wonder now what has become of the kids we played with. All that we can do is to say a prayer and hope that their families have survived the destruction.

The eight-year long war fought between Iran and Iraq left both sides depleted of its culture, heritage and people. By 1984, all those foreigners who were invited by the Iraqi Government, were sent back and the country steeped into an economic and political rut. Hundreds and thousands of people died and many were left with a future that was bleak. Iraq is a standing testimony to what greed and arrogance can do to one’s world. The region, earlier known as Mesopotamia, was the cradle of civilisation and culturally very fertile. History documents this region as the land where the first writing system has been invented, the land where Mathematics, Astronomy, Medicine originated and was known as ‘Cradle of Civilisation’. Today Iraq’s political situation has changed hands but the horrors still continue. There are several such nations across the globe whose political and social situation is no less horrific. We are losing the world and its people, the rich heritage and their oral histories to our egos, arrogance, greed for economic wealth, political power and communal hatred.

The pandemic we are witnessing now has put a lot of things in perspective. It has definitely proved that there are more important things in this world than our petty squabbles. Now is a great time to understand and teach our children the value of life. You can only fall in love with people when you read and understand different cultures, their histories, understand their pain, share their laughter.

Sometimes a simple weapon is enough to win the greatest war.