The lessons of discrimination and caste prejudices were as carefully taught to us as they would, the life lessons, to a child. Growing up in a very orthodox and conservative Brahmin family in Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh, we were introduced to caste discrimination and status at a very young age. The instructions were so important to follow that when I think back, I don’t particularly remember being taught any other life skill or talent by the elders in the family as seriously as they have instilled in us the importance of being a Brahmin. It is ingrained into our psyche that it is only after several menial births that one would be born a Brahmin. We are told that we should be really thankful that we are born into one this time as it is very noble and sacred to be born a Brahmin.

So when the first time I went (without taking my grandparents’ permission) to a ‘non-brahmin’ friend’s house in my 8th std for her birthday lunch, I was shocked to know that their food smelled and tasted so good. And her parents were such warm people and more importantly, nothing happened to me when I sat on their couch or shared a meal with them. It dawned on me and my sister that maybe what we are being told was not true. This was the beginning of so many more revelations about caste discrimination that my family strictly followed.

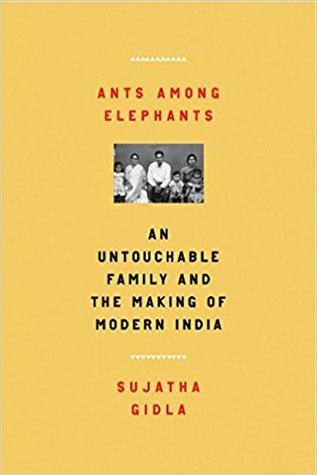

The memories painfully came alive when I started reading the memoir of Sujata Gidla ‘Ants Among Elephants’. Sujata Gidla’s memoir is one of its kind. It is not only a personal narrative, it is also a record of the long history of class conflicts, discrimination and untouchability that is rampant in India and specifically in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. She takes us through the last few years of India’s freedom struggle followed by attainment of Independence, Christian missionary work in Andhra Pradesh, Reorganisation of States under the helm of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the Nizam rule, the rise of Communism in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, the birth of Peoples War Group, the trends in Telugu Literature, and many more political, social and literary currents in the Telugu land. After a decade-long labour, research, interviews with family, friends, fellow untouchables, she finally came out with the book in 2017.

Now living in New York and working as a conductor on the New York City Subway, Sujata traces the painful history of her family starting with her great grandfather, who belonged to a nomadic clan devoid of any caste affiliation. So when they were forced to give up their nomadic life and settle in a village, they were naturally shun to the bottom of the hierarchy, that of an untouchable. Sujata is very candid in attributing her education and employment opportunities, and her arrival in United States of American in the 1990s, to the Christian missionaries. The converts were educated in missionary schools established all over Andhra. It was her grandfather Prasanna Rao Kambham, who first converted into Christianity which subsequently opened doors for the successive generations in the family like herself to reap the benefits of the opportunities.

People’s History: Indian history is silent on the condition of economically deprived, marginalised sections of the society and especially Dalits. History text books glorify the stories of a few leaders and their political power and administration, ignoring hundreds of others who have been marginalised. In the contemporary times, there has been a shift in the reading of history, and ‘History from Below’ or ‘People’s History’ is being emphasised to understand the impact of socio-economic and political changes of a country. Mass movements, political conflicts, peasant movements etc. are all being read and understood from the grassroots level. The hegemonic groups, power politics of a few power-hungry politicians etc are being questioned. Personal narratives thus bring out the saga of a common man, his trials and tribulations. At a time when personal histories are gaining importance, ‘Ants among Elephants’ brings about a paradigm shift in the way Indian history and politics is understood. Though many social scientists, economists, historians have documented the historical and political dynamics of India, they have failed to document the lived history of the Dalits.

Through the story of her maternal uncle K G Satya Murthy, Sujata recounts the history of the untouchables. The memoir is a biography of his life from a shy boy to a spirited youth participating in the Indian freedom struggle, an ambitious youth leader to co-founder of the People’s War Group in the 1970s. Her account is a historiography of the age that was indifferent to the voices of the marginalised, an age which was preoccupied and was busy building a new India, and an age where more than half the country woke up to the see that they don’t have a share of the upper caste ‘Nationalism’. So Sujata writes her own history documenting names of various untouchable castes, their traditional occupations, voluntary conversions of many Dalits into Christianity, the double marginalisation of the converted Dalits in the Hindu dominated society, festive and family gatherings with their customs, rituals and cuisine, recording the life of the community she belongs to.

Sujata’s mother Manjula is an active witness to her brother Satyam’s life and ideology. She grew up in the shadow of her brother imbibing the lessons of self-esteem, importance of education which she passed down to her own children. Her story runs parallel to that of Satyam’s in the memoir, adding a woman’s perspective through her struggles as a girl growing up with very powerful brothers, Satyam and Carey. Her role in the family was that of any other girl in the Indian society, grappling with the male-centred customs and expectations of the society.

Candid and forthright, the memoir is one of the most powerful stories of modern India.