Summer is the time jasmines (malle in Telugu) flood the flower markets in South India. It is a busy and prosperous time for the flower merchants in every town and city and these beautiful, fragrant flowers adorn every occasion in every home. Malle has an important place in Telugu weddings. They are used for garlands of the bride and groom, to decorate wedding altars, and, not to forget, for the bride’s poola jada (plait adorned with flowers). I know many of my friends who got married during the months of April/May, daring the sweltering heat of summer, just to have loads of malle for their wedding.

My mom Savitri a few days after her wedding (1962)

A few days back I was going through my childhood pictures and my daughters were fascinated with pictures of my sister and me with a poola jada and dressed in traditional attire of pattu parikini (a Kanjeevaram long skirt and a blouse worn by girls on festive occasions). It was almost a ritual during summers to get a flowered plait done at least once. Every summer, my mom would set a date for us to get the poola jada done using the malle flowers that were abundantly available in the market. The program involved meticulous planning and my mom took it very seriously. One particular variety called boddu malle was very popularly used for the poola jada. My brother would be sent to the local flower market in Vijayawada to meet one particular vendor for the ‘best’ boddu malle buds for that perfect jada. He would buy a couple of kilos of them early in the morning. Then my mom would inform a lady who was a distant relative, who specialised in the art of making poola jada. The lady would arrive post lunch and then the important task would start. She was treated with utmost respect and everybody in the house danced attendance around her serving her coffee and snacks and generally keeping her happy.

If you ever harboured a fascination to have a poola jada made for your hair, one absolutely essential criteria was to have long, thick hair – ‘long’ because the poola jada would not look good on short hair; ‘thick’ because if you had thin hair, you would end up with a terrible headache owing to the weight of the poola jada. For those who had neither of these, a hair extension was used to make the plait look longer and thicker, with several knots and elastic bands all along the plait to keep it in tact. Today, as a matter of convenience, ready-made poola jadas are used for brides and flower vendors take orders even a few days before the wedding.

The making of poola jada involved several hours of patience and concentration. First our long hair was neatly plaited till the end which was then adorned with a hair accessory called jada kucchulu (an accessory used to enhance the beauty of the plait). Each malle bud was selected with care and with the help of a white thread, the buds were made into garlands. These garlands, made in different lengths, were then sewed into the plait right from the top of the head and along the length of the plait, carefully tucking away the flowers into beautiful designs. Sometimes other varieties of flowers in different hues like roses and kanakāmbara were used along with malle for added beauty. The lady would take a couple of hours for each of us which meant the entire episode went till 7:00 in the night.

The activity didn’t end there. After the poola jadas were made, my mom would make us wear the traditional pattu parikinis and the gold jewellery while my dad or grandfather would get ready excitedly with their camera, ready to capture the moment. I remember my sister and me grumbling all along for the silliness of the situation. The only fun part of it all was the fuss the elders made around us. We were suddenly treated with a lot of importance and we were fed dinner by my mom or an aunt, narrating a story or two to divert our attention from the discomfort. Bedtime was an agony with capital ‘A’. Lying down on the bed, with the poola jada carefully placed to the side, we spent the rest of the night in just one single position and invariably woke up in the morning with a stiff neck and bleary eyes from lack of sleep. The poola jada lasted the entire day and we would have a dreadful time taking bath and generally going around with the heavy thing following us everywhere.

I remember a couple of weeks before school closed for summer, some girls in the school would come with poola jada and school uniform to go with it!!! It was a common sight in school during the pre-summer-days and teachers didn’t mind girls coming with mehendi designs on their hands, heavy silver anklets over their school shoes or flowers in their hair along with black ribbons. It was a sight to behold!!

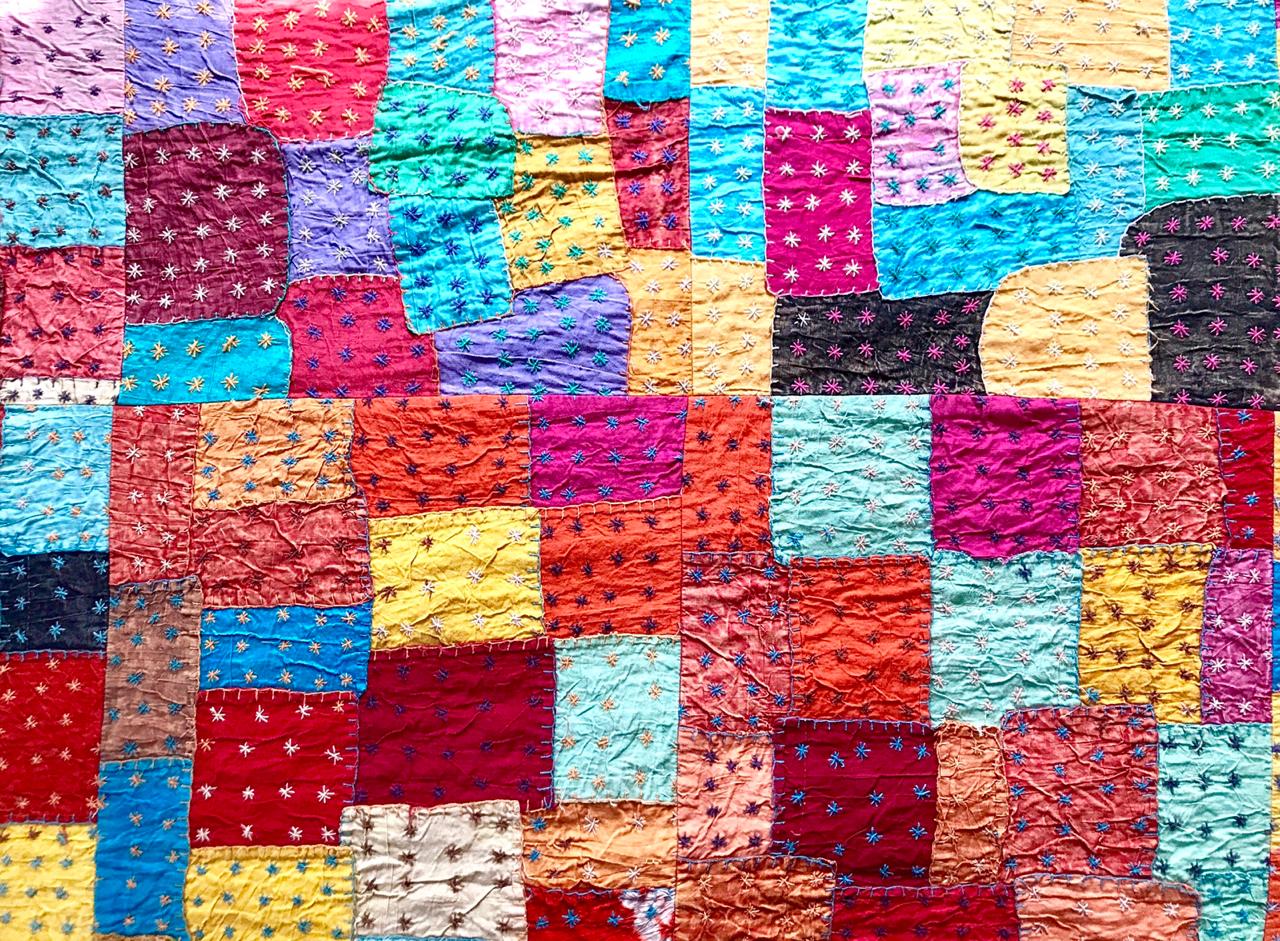

Ready-made poola jadaas (image courtesy: Valli, my friend from Vijayawada)

I must confess here that my sister and I never actually craved to be part of these occasions since it would only mean two days of discomfort. We would just find ourselves in the middle of one every year, because the fun and amusement derived from these gatherings were purely for the adults, who absolutely enjoyed such occasional digressions from their routine life. But over the years, the nostalgic person that I am, I find the experience really unique and a significant part of growing up, carrying with it the essences of the bygone days.